By: The Turjeman

I should begin with a warning: This essay the most accurate description possible of the Christianity in which I was raised. Whether you agree with it or not, it is an honest portrayal of the culture of my childhood.

As such, you may hate it or you may love it. Regardless, I suspect that many readers will recognize this as authentic.

If any audience deserves a content warning, it’s perhaps best split between Christians and Jews:

- For Christians: This essay contains detailed descriptions of the specific kind of Christian doctrine and practice in which I was inculcated, down to the most petty detail. So this may be offensive to those who would prefer not to think about questions about or challenges to their faith. Read this at your own peril.

- For Jews (especially religiously minded or observant Jews): You may be shocked by the images and by my flagrant use of Christian terminology. I’m going to spell out some words that Jewish tradition cringes at. The chilling factor that exists within Judaism would prefer that we never discuss these details, as if some other Jew will be attracted to this description of the evangelical message.

But since I am an observant, religious Jew now, nothing could be more absurd. No person in their right mind will read this and end up thinking that they should be a Christian.

Perhaps I should begin every essay on this blog with a trigger warning:

“Warning: the contents of this essay is certain to offend someone.

Some may be offended by the very concept of content/trigger warnings.

Reader discretion is advised.“

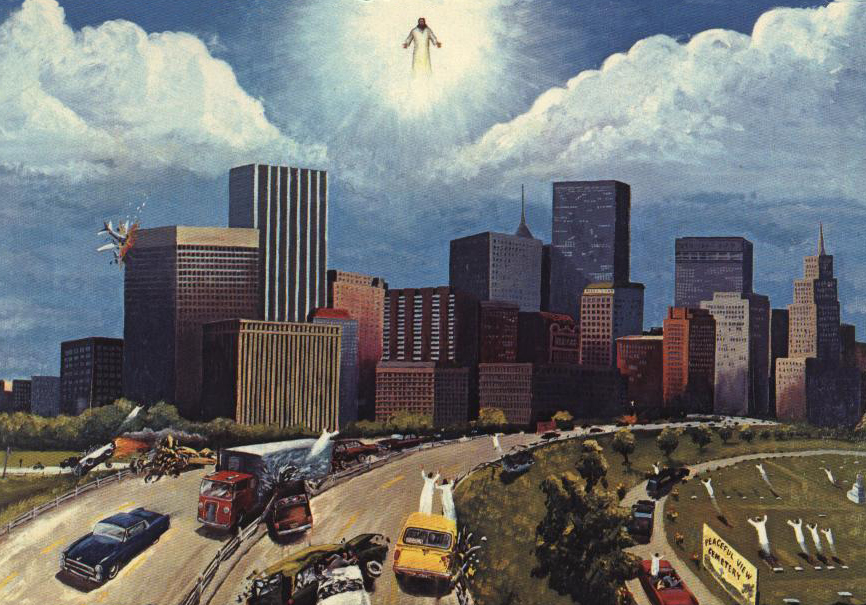

Now let’s look at this truly horrifying painting: The Dallas Rapture.

This is one of the most memorable images of my childhood. I saw it often, and it made perfect sense in my home, church, and school environment. Even though I now know that it is set on the 1970s skyline of Dallas, Texas, it vaguely reminded me of a bend in the highway of the city where my family lived at the time.

For those Christians who believe in something called The Rapture (which certainly is not a consensus), it is supposed to be a world-shattering event. What this painting portrays is supposed to be a moment of extreme joy, but for others, this is the beginning of the apocalypse.

That’s a pretty succinct summary of the Christianity of my childhood: a strong theoretical happiness about being right with God, mixed with a wide plethora of fears and horrors about the present state of the world, and of what it would inevitably become.

[Look at those driverless cars and pilot-less airplanes crashing. Look at those dead bodies bursting out of their graves. This is a horror show. The Dallas skyline has since improved as can be seen here. Spoiler alert: Jesus has not yet arrived, and now has a list of competitors.]

[Stardate -298017. As begin writing this, it’s 25 December 2024. I’ve been For good while, I have been inspired by contemporary, ongoing stories of different people who have successfully escaping oppressive religious milieux, and who are finding some other framework with which to understand life. (By successful, I mean: walking away and not being murdered.) If I were to offer you a crash course, I would say to start with Yasmine Mohammed’s life story [eventually, and an affiliate link] and her podcast [add URL] – or corresponding YouTube channel). Besides her I should also mention Sarah Haider, Mohammad Tawhidi, and Christine Rosen. But this list barely scratches the surface.

(Jewish examples: Rabbi Asher Wade, … but also Shulem Dean, Goldy Landau…)]

What I am attempting to put together here, in this “blogue”, is not only a story of a conversion to Judaism, but also a slow, hesitant deconversion from Christendom and from Christianity, over the course of a few years. I believe that this part of my life story is as important if not more important than my conversion to Judaism: since that part is not agreeable to everyone, nor should it be.

So, let’s set some ground rules for this particular posting.

- This one isn’t about Judaism.

- This isn’t about bashing religion in general. You can find that on other sites; not particularly here. I’m still working on my complicated relationship with religion.

- This is going to be about some cold, hard facts: data gathering. This is about a snapshot of a particular religious approach to life at a particular time and place.

- This is not going to be anecdotes that happened in the church-school compounds where I spent most of my youth. Oh yes, I plan to cover that story fully in separate entries, in hopes that other people being raised in Christian communities (anytime between 1970 and 2020, basically) can find some common ground.

[

A few months ago, I was asked asked to speak to an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood group about the process of my conversion, tangentially related to the holiday of Shavuot and the story of Ruth, who is one of the most famous converts to Judaism. While preparing that presentation, I decided it would be useful to define where I came from, in the terms of faith and religion. This entry is an attempt to describe that “place” completely and accurately, and in fairness to the doctrines and practices.

Then, by coincidence, I met a Christian man from my home environment here in Jerusalem. So several variables were changed…

(By the way: if you are reading this article and I didn’t personally invite you to do so, please send me a message at the.turjeman@gmail.com and tell me so. I’m not looking for a “like, share, and subscribe”. I simply would like to know how you found it, since I’m not advertising it and don’t truly expect it to be noticed by anyone at this date. This is still a project in the works, but I am curious whether search engines are picking it up. If I start getting spam at the the.turjeman@gmail.com, I’ll know it’s getting out there somehow.)

This is a chapter that I’ve been working on for a while: how to define the particular brand of Christianity that I grew up with, which was Fundamentalist, Independent Baptist (defined below) churches and schools, located the US Southeast during the 1970s and 1980s.

In the title I say “our” Christianity in scare quotes. I might say “our” beliefs or “our” church in this article. Please understand my meaning as: those of myself and my family back in the day . All I’m doing here is making a record of how everything was taught to me at home, and church, and in Christian schools growing up. It’s no longer “ours”; it’s certainly no longer mine.

This was all before I converted to Judaism and moved to Israel. But for me at the time, this was the only kind of Christianity that existed. Many people raised in Christianity in the US will find my explanations here extremely familiar. But these are not universally accepted definitions — far from it. As I progressed in my life, I met more and more people whose Christianity was extremely different from my own.

Much of what follows can all be refuted, as well it should be. If you disagree with any of the following, please don’t “come at me” for getting it wrong: I also disagree. I may also be mistaken about some things that I misunderstood at the time. I appreciate and welcome correction of factual errors, but I have no desire to enter into doctrinal debate.

[Since those years, I’ve met all kinds of Christians. And then I met Jews, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists. I have extensively studied the wide variety of Christian denominations, and other religions extensively. I have learned to distinguish minute points of theology, doctrine, laws, and local customs, comparatively between them.

My point being, even if I write the following as if this was my faith, it is no longer.]

So, with all of those provisos and user content warnings out of the way: Here goes.

My mother and father came from rural, agricultural families. She was raised Southern Baptist. My father was raised Methodist.

When I discussed this with Rabbi Asher Wade several years ago, he joked that have been a major conflict between their families at the time. I honestly don’t know, because that was slightly before my time. I think my parents’ families were not heavily involved in judging them. My parents eloped, got a marriage certificate with no witnesses from a well-known community pastor who gave them a private marriage ceremony, and found a way to make it work despite those minute denominational differences. [Footnote: They literally called the preacher out of his farm work. This is a separate story, and worth investigating in the context of an agricultural community in Georgia. But that’s not the point of this article, which is denominations and faiths.]

By the time I was three years old, my parents had already discovered something new and great, for them: Fundamentalist, Independent Baptist churches. (Henceforth referred to as FIB.) This was a quasi-official term, used by many churches, each word having a specific meaning:

Fundamentalist, meaning: the foundational beliefs of their faith were based on a collection of quasi-official opinions from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in reaction to the new scholarship of the time. I’m no expert about the origins, but from my review of a lot of historical literature about what defined “Fundamentalism”, including the set of books in my ancestral home titled “The Fundamentals“, the major points seem to have been:

- The divine inspiration of the Bible, and the belief that it has no mistakes (inerrancy)

- Rejection of higher Biblical criticism, e.g. Moses being the only author of the Pentateuch; only one author of the book of Isaiah

- Rejection of various theories of Evolution, such as Lamarckianism and Darwinism

- The virgin birth of Jesus

- The historical reality of Jesus’s miracles

- The belief that Jesus’s death was an atonement for sin

- The literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus after his death, i.e. despite the books in the New Testament that are unaware of it

- Attempts to reconcile the contradictions between the four canonical Gospel books

- Various opinions about evangelism and foreign missionary efforts at the time

- Attempts to reconcile new archaeological finds in biblical lands with these beliefs

- Attempts to reconcile modern (at the time) science with traditional faith

(This is all great territory for exploration, and you wouldn’t be blamed for seeig similarities with Rav Nathan Slifkin’s movement in favor of rationalist Judaism. But these are topics for another day.)

Independent, meaning: Churches were not members of the Southern Baptist Convention. So they were not obliged to conform to anything imposed by a larger, governing body.

Baptist, meaning:

And my parents’ attraction? My mother explained it to me as follows: Southern Baptist churches were cold and dead, following some tired rituals, and there was little depth to the teaching and preaching. Whereas, in FIB churches: people were awake and alert, taking notes during classes and sermons, asking questions, and engaged in meaningful conversations.

Given where they came from, I can’t fault them.

What did it mean to be a Christian? This was the central question of our lives. We were required to know the answers and to believe them, because belief was the core requirement. In Judaism terms (l’havdil), there were only two mitsvot (commandments): one was to believe in the beliefs, and the other was to convince other people to believe in the beliefs.

We were expected to explain our faith to other people: both to people who were already Christians: in the form of giving one’s “testimony”. And more importantly to people who were not Christians: in the form of “witnessing”, also known as “soul winning”. Because the primary objective of every Christian was to make another Christian.

(“Wait a minute,” some of you might be asking. “This sounds too simplistic. What about the Ten Commandments? What about attending church?” For the answers, read on.)

A Christian was a person who had chosen to believe that the human-born Jesus is God, and had accepted him as their “personal Lord and Savior” with full sincerity. This moment of decision was also supposed to be accompanied by a confession of one’s past sins and a resolution to stop committing those sins.

Or as we were often taught as children: The “ABC’s of salvation” are:

- Accept (or Admit)

- Believe

- Confess

This is a simple formula for teaching children something that’s overly complicated for them to actually get, but supposedly enough to get them in the door, so to speak.

Knowledgeable Jews will recognize here the Rambam’s principles of teshuvah. He didn’t invent them, after all: he was enunciating well established facts in ancient Judaism, which Christianity borrowed from.

Another popular piece of simplistic evangelism was known as the “Romans Road”: a series of sentences taken out of context from the epistle to the Romans by Paul, used to simplify Christian beliefs about “salvation”. I’m not going to dignify this idea by providing a link to it; search at your own time-wasting peril.

What is this “salvation” of which I speak? That’s another term of jargon. It means having your soul saved from eternal damnation in Hell, aka the lake of fire, which is what it’s going to get if you don’t “get saved”. “Being saved” is complicated to understand, although it’s often used as accepted currency, assuming that everyone knows what it means. We referred to any Christian as “saved”, and any non-Christian as “not saved” or “lost”: meaning, on their way to a certain eternity in Hell: “Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched” (Mark 9:44).

To further describe “salvation”, here is something else that we picked up along the way: a catchy aphorism known as “the three tenses of salvation”. “I was saved [i.e. at the moment of my belief-acceptance decision], I am being saved [i.e. as an ongoing process], and I will be saved [i.e. at the moment of death, when instead of going to Hell I will go to Heaven].”

Being “lost” was considered the most regretful and pitiable existence possible, a combination of ignorance hopelessness. It could only be cured by mansplaining (or womansplaining) the basics of Christianity to someone who had obviously missed out on the simple gospel message.

I am skirting around the important distinction between Armenians (who believe in free will, but also that salvation is not permanently guaranteed and can be lost) and Calvinists (who believe in determinism and predestination, but that salvation once acquired is permanent and cannot be lost).

Considering all the arguments and deaths that happened over this basic point, the countless number of hours wasted in angry discussions, it’s a real cop-out for me just to drive over that speed bump, right? But this isn’t the time or place for that. If I get into this topic, we will be stuck in the weeds for hours. Many people have debated this topic and have been killed for disagreeing about it. So: no, thank you.

My FIB childhood Christianity was a hybrid of Arminianism and Calvinism: out of free will a person can choose to accept Jesus, and then the salvation is permanent and eternal. I don’t know who came up with this solution, but she deserves some kind of eternal prize.

As if any theologians were listening to women at the time! This is one detail about FIB culture I have not yet mentioned: It may shock you to know that it was not very feminist. There was a heavily reliance on one verse, 1 Timothy 2:12, to enforce the basic patriarchal society that already existed.

“Being a Christian” therefore was being a person who had this ongoing process running in their life. At that initial moment of becoming a Christian, all their sins were supposedly forgiven by God, unconditionally, with a guaranteed entry to eternal life in Heaven. (And yes, we often faced the problem of the theoretical deathbed conversion moment of a mass murderer, Hitler, etc., which didn’t seem fair but, hey! “God Moves in a Mysterious Way” as the old hymn says.)

Then, as part of being a Christian, they were supposed to improve themselves, study the Bible for better understanding, constantly work on eliminating sin, and of course: convince more people to become Christians.

It was well known that every human being sins. But that initial cleansing of one’s sins “with the blood of Jesus” / “with the blood of the lamb” (and other confusing metaphors, such as being “washed as white as snow” in an old-school reference to Isaiah 1:18) only took care of forgiveness of sins up to that moment. Christians were supposed to keep working on themselves, in something analogous to the Jewish concept of avodat haMiddot (working on character improvement). Examples would be: continually engaging in study of the Bible (as mentioned), attending church services at every chance possible for further education and moral support, and perhaps even entering full-time Christian “service” as a teacher, preacher, pastor, evangelist, missionary. Or a song-leader: the person responsible for teaching and leading hymns to the choir and to the congregation.

In my family, we attended church services three times a week: Sunday morning, Sunday evening, and Wednesday evening. My parents also sent me to church-run schools from age 5 kindergarten until I graduated twelfth grade, five days a week. So I got my fair share of indoctrination and brainwashing, “scripture memorization”, and moral preaching for six days a week. Saturday was the only week that I ever had any relief, and Saturday morning cartoons (in a limited amount) were my escape from reality.

Let us speak frankly: what about being a good person? Does that have anything to do with Christianity?

One could also scour the Bible for “good deeds” to practice, but “good deeds” always had a whiff of heresy about them. Because only heretics believed that they could “earn their salvation” by doing good deeds. No: salvation was given freely, Jesus was always guaranteed to forgive the most unforgivable sins, and Christians were supposed to simply want to be good people. Because salvation also came with a guaranteed soul upgrade that resulted in an improved character.

And yet, Christians read their entire “Bible”, which includes both the Scriptures of Judaism (the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings), which is chock full of laws and moral teachings, and an their “New Testament” which basically says: throw the Old Testament laws because Jesus nullified it all.

To put it in Jewish terms, Christianity practically doesn’t have any mitsvot, i.e. commandments that they are expected to fulfill. In that theology, all the commandments were annulled at some point in the “New Testament”, and instead of being “under the Law” as in Judaism, they are supposedly “free in Christ” and under no obligations to obey commandments. This is not a water-tight belief, however, because there is that one major obligation mentioned earlier: to spread the gospel and lead non-Christians to become Christians – in a word: proselytizing, although they would not use that slightly cynical-sounding word. It’s also a bit problematic to say that Christians have complete freedom from the Law (i.e. the 613 commandments of the Torah), because they take some of them very seriously. They pick and choose which ones are important.

If you are confused at this point, congratulations. The spirit moves in mysterious ways, saith the prophet Bono.

Outliers

I met a couple of childhood friends who, in retrospect, helped me make sense of not being within this pre-defined belief system.

One was a Muslim boy whose family had moved to the US from England. He was dark-skinned, so I’m going to guess that he was South Asian in ethnic origin, just a hunch. He attended my Christian school for a few months in third grade (around age eight), and was a sweet boy. I liked him for his “otherness”, a complete mystery who was different from all of us white and black rednecks in Florida. I wish to God that I could remember his name so that I could look him up today. If I understood the situation correctly, his parents chose to send him to this Fundamentalist Baptist church-school because there were no Muslim schools available back then, but they wanted him to be in a morally strict environment.

Once, our teacher asked him what was his favorite Bible verse, and he cited the hymn “Whiter than Snow“, which we used to sing in class. He didn’t have a “Bible”, nor would he. He didn’t know the difference between a Bible verse and a Christian hymn being sung during the 8:00a.m. Bible class. So some children laughed at him when he said that. Later, I overheard our teacher say that she needed to buy him a Bible. Of course, it would be a 1611 King James Version Bible, just as Moses used when he led the Children of Israel out of Egypt through the wilderness.

One day, this English Muslim boy turned to me outside of class and said in his British accent, “I shall never see you again.” He was leaving the school. Apparently his parents had found a Muslim school for him, or had figured out that he was being brainwashed.

I was simply confused. This boy was speaking matter-of-factly. We weren’t smashingly great friends, but now there was no chance we would ever be. What child at that age can just say that with so much certainty? Decades later, that moment is burned into my brain.

Another friend I met in seventh grade, whom I will call here Giosuè. Giosue and his brother hailed from an Italian, Roman Catholic family who moved into our city of Custer’s Grove, Georgia as restaurateurs. Again: their parents had few other choices if they wanted to put their children in a moral Christian environment, because the local Catholic Church at the time barely had an educational program. So here was Giosue, confident in his position in society an in his religious faith and sense of belonging, and we Baptists were the outsiders.

It took us a while to develop a great friendship, since I was naïvely so convinced of the correctness of my own faith, but this friendship became foundational as the years went on. Today, Giosue is my closest friend, and the person that I refer to here as my Consigliere. I initially resented the doubt that he introduced in my religious practice, but now I know that it was exactly what I needed.

Giosue and I were both attending this Fundamentalist, Independent Baptist church-school, which had a “Bible class” four days a week, plus a “chapel” class one day a week, and regularly invited evangelists to speak to us. There was little distinction between these preacher / evangelists’ speeches and a sermon that they would give in a church to an adult congregation.

What this means in practical terms is that a preacher is screaming and yelling for an hour at schoolchildren, whose parents have paid good money to get them a private school education. These parents are all churchgoing Christians. But these evangelists are preaching angrily at their children on a weekday morning as if they are “sinners and publicans” to use the New Testament terminology. This includes an “altar call” in which the preacher challenges the children who aren’t yet Christians to become Christians. (Take a moment and reflect on the absurdity of that idea.)

With Giosue, one particular occasion is burned into my memory. There was one of those typical evangelists who came to speak to us at “chapel”, and asked students who did not know for certainty that if they would die today, they would go to Heaven, to raise their hands. This was a typical “altar call” or “come to Jesus moment”, practiced over and over, ad nauseam in every Baptist church service. But very few preachers actually ask the congregants to admit their doubt.

So Giosue did so: he raised his hand, indicating that he was not certain that he was going to Heaven when he died. Because he was a Roman Catholic, and he did not believe like Calvinist Protestants that a person could have “assurance of salvation”. While I disagreed with him at the moment, I was sitting beside him, and thought that was pretty brave. Because the evangleist came by, got down on one knee, and asked him why he was in doubt, and he explained his belief.

Giosue was occasionally taunted by fellow students in our school, and occasionally confronted by teachers who told him that he was certainly going to hell for his Papist beliefs. I don’t know how he put up with this taunting, but he and his brother hand a coolness factor that overruled all social status that really mattered. (I was about to used the word “trumped”, but that would lead to confusion in the current usage of the English language, Stardate -298213.)

Giosue later abandoned his religion, just as I abandoned mine. But we bonded eternally on these formative childhood experiences. We compare notes often, survivors of psychologically abusive religious childhoods, trying to find the best way to live now as we approach becoming middle aged.

This is what he says in retrospect about those years, attending a Fundamentalist Baptist church high school, while being part of a Roman Catholic family. Specifically, about the evangelist doing the hands-up altar call:

“I do remember that. It wasn’t the first time I engaged in a conversation like that as a kid. At the time I felt just as convicted as a child of Roman Catholic parents. We were raised to believe that the Catholic Church was the ‘One True Church’.

I also remember getting into that similar conversation with Mr. H…. [a teacher] a couple of times. I didn’t just have those conversations with our elders. Sometimes a student would ask me why we worship statues and ask me, ‘Don’t you know you’re going to Hell?’ C….M… [our English teacher] never treated me that way. Neither did Mrs. S…. [our more open-minded Spanish teacher]

But what struck me as odd with the Bible-thumpers was that they were basically preaching that only God can judge human beings souls. But at the same time, out of the other side of their mouth, they would talk about how they knew 100% how they were going to be judged and how non-believers were going to be judged. I always thought that was very contradictory.I will say that as a Catholic kid, we were not taught that other Christians were going to Hell. We were just taught they were in the wrong side of Christianity, but God might have mercy on them upon their death.

It used to really upset me that a grown-up would tell me that if I don’t change, I’m definitely going to Hell because that’s what the New Testament says. I mean: I’m glad they liked a book, but I just didn’t believe that good people could go to Hell just for not reciting John 3:16.” [Editor’s note: John 3:16 is also in the Latin Vulgate and in the Douay-Rheims Bible, but Giosue seems to be saying that Baptists were particularly militant with this specific verse.]

Giosue was not a big fan of the Hitler-on-his-deathbed, final regret confession come-to-Jesus moment scenario. And we seriously talked about that in eighth grade at age 13 years old: you know, like healthy children debating theology.

Christianity: the tautological definition

Back to my family, and to our Fundamentalist, Independent Baptist churches.

“Christianity” was defined as “the fact of being a Christian” or “being in a relationship with Jesus” or colloquially “having Jesus in your heart”. Christianity was not considered a religion, nor an institution, nor a legal entity. It did not depend on race, nationality, or socio-ethnic labels, and it could not be passed on to children. My people bristled at anyone who would suggest otherwise: being a Christian was a one-time choice left up to the individual (although it would be highly embarrassing for a child in a family of Christians not to be one, similar to what Orthodox Jews call “going off the derekh“). In one popular saying, each person was called “a child of God”, and “God has no grandchildren”.

Therefore, you would get in trouble around my people if you referred to Italy as “a Christian country” or imply that the Armenian residents of the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem are Christians as opposed to the Muslims, in the overwhelming Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem, which is much more than a quarter. You would get in trouble for using “Christianity” to refer to the Eastern Orthodox or Roman Catholic Churches, which are religious institutions.

And hell hath no fury like a Christian being told that they were “religious”, or that among the different religions of the world they had chosen Christianity as their “religion”.

In one of the final discussions that I had with my mother about the subject, I referred to Christianity as a religion (because I was using standard English, and comparing some points in Judaism), at which point she seethed angrily, “It’s not a religion! It’s a relationship!”

Because like “good deeds”, the word “religion” also had a stench to it: it implied dead, meaningless ritual.

In this mentality, there was no such thing as “meaningful ritual”, performed with kavanah (Hebrew for intention, purpose, or direction). May as well have been an oxymoron. And a person referred to as religious may as well have been sarcastically called a “holy joe”.

And so I found it very refreshing to find in Jewish circles that the term “religious” has a positive connotation: it means being observant of Judaism, with intention. Presumably for the right reasons. (Among my people back in the day, that concept was called “being spiritual”.)

What I have described above was and still is very common for a particular slice of US culture, which considers itself to be the authentic belief, understanding, and practice of that whole hodgepodge of confused histories about Jesus, rambling letters, and hallucinogenic trips known as the “New Testament”.

As I later discovered: there is no one Christianity, only myriad versions of Christianities. And so it has ever been, since approximately the year 70 CE. There never has been one true, unified, catholic (with a small c) church. The major brands have co-opted the name, but none have been the original authentic one. Because it never existed.

It was a course by Dr. Bart D. Ehrman, titled “Early Christianities” that finally allowed me to understand and accept this reality. As I went through his course, I had a moment of soul cleansing such as Yasmine Mohammed describes in her book “Unveiled”, when she finally understood that Islam is a human-made religion with arbitrary rules. The feeling of freedom and acceptance of reality was indescribable. For Yasmeen, she was in fear that her mother could condemn her to Hell, or that her al-Qaeda ex-husband could summon her to Heaven as his chosen wife for eternity, or that walking into a bathroom incorrectly and without saying the proper prayers would endanger her with demons.

As for me, I have been made to feel guilty for decades for not being certain in my beliefs, for doubting the fundamental principles described above. I would still be nursing that little doubt in the back of my mind: “What if I’m wrong, and what if I am destined to Hell for all eternity, ‘Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched?’”

Guilt is the gift that keeps on giving. But if God wants me to accept a faith on those terms, I say “no thank you”.

Leave a Reply